In Traitor’s Purse, Allingham gets the pace and tension deliciously right, yet she wrote it in fragments in 1940, in between air raids – and created a wartime masterpiece.

See below for an article by A. S. Byatt on Margery Allingham, in The Guardian.

This is, I think, my favourite detective story. I return to it again and again, just as soon as I have forgotten enough to re-enter it. The novel has the most amazing plot of any thriller I know. It was written in 1940 at the beginning of the second world war and has an ingenious secret at its centre, which I am not going to give away in case there are still readers who can come to it as the surprise it should be. Allingham’s publishers queried the plausibility of the German plot she imagined – only to discover many years later that she had in fact imagined a secret that did really exist.

The story is not only staggering because of the secret. It is staggering because in the opening pages the urbane Mr Campion is discovered in a hospital, having completely – or almost completely – lost his memory. He knows only that he has to discover and prevent something monstrous, portentous and urgent. The combination of these two strands creates a tension that I’ve never experienced in any other book I have read. The story takes place in Allingham’s own world of the bizarre, the minutely weird, with queer and memorable names, all threaded into formal dinners and police procedures. When reading discussions of Allingham, I have been shocked to find her being criticised for failures of realism. She creates her strange worlds with their own odd structures alongside what we think of as real.

Allingham is in one way an English writer like Lewis Carroll or PG Wodehouse in that she makes her own kinds of gangs and villains alongside “realism”. All detective stories, I suppose, are unreal because they have strict rules, and each of her books has different rules, depending on the small world it explores – fashion in The Fashion in Shrouds, the magical and sinister countryside of Sweet Danger, the post-war blocks of London flats in The China Governess, the dancers in Dancers in Mourning.

As an adolescent I puzzled about how the tradition of the gentleman detective came about. There they all were, urbane, watchful, inane from time to time, with steely, independent intelligences under their surface smoothness. Dorothy Sayers said that Lord Peter Wimsey was a combination of Fred Astaire and Bertie Wooster. With each appearance he became more complicated and human, and in the end Sayers was accused of having fallen in love with him. Campion was invented, according to Allingham, as a parody of Wimsey, hiding an aristocratic background under a pseudonym. Both had menservants full of character – Wimsey had Bunter, who had kept him alive during the first world war, and Campion had the brilliantly named and wonderfully realised ex-cat-burglar, run to fat, Magersfontein Lugg. These characters derive from Wooster’s Jeeves, the all-knowing, all-efficient manservant, working to totally trivial ends. If Wimsey becomes human when he sees Harriet Vane, a crime-writer, being tried for a murder she did not commit, Campion becomes human when his superficial memory disappears, leaving his real self naked to his real feelings. His need not to divulge the state he is in to his future wife, Amanda Fitton, is necessary for the story, but Allingham makes it very moving, as she does when Lugg diagnoses what has happened to him.

I once had the idea of a book about novels written in wartime, when, in a sense, endings were impossible, because they were unknown. Elizabeth Bowen did not publish a novel during the war (and turns out to have been engaged in all sorts of secret war work), but in 1941 she did publish an uncanny collection of stories, Look at All Those Roses. I didn’t think of including Traitor’s Purse in my book, mostly because on a first reading I thought Allingham had so perfectly made a shape and a story to contain a wartime narrative that it must have been done with the help of cool hindsight. Not a bit of it. It was written and sent in for publication in 1940, when bombs were falling every night.

She was living in D’Arcy House in the centre of Tolleshunt D’Arcy, in Essex. Her husband, Philip Youngman Carter, known as Pip, came and went from London. Their life was superficially happy, with large parties, as in The Beckoning Lady, another of her novels in which bucolic charm and hidden ugliness mingle in complicated forms. Allingham had been nervous about taking part in village life; the war changed that altogether. Their house became the air raid precautions post, and Allingham found herself taking on a whole new life of administration and distribution of gas masks, splints, spades, buckets, rubber boots and so on.

The coming of gas masks in particular marked the transition to a wartime world. At first there were no masks for babies or the elderly, and the country people wondered how the cattle would breathe without masks. I remember as a small child sitting by the fire turning this alien thing over in my hands, not really knowing what it was for. They were sinister, khaki contraptions, bristling with straps and buckles, that made you look like a monster. We had to carry them through the fields to school. My baby sister did have a mask – it was, as I recall, a garish, cheerful red in colour, an egg-shaped receptacle with a window, into which she could be stowed.

Allingham was involved in the reception of the 90 unaccompanied evacuee children that the village had been told to expect. When they arrived, there were eight busloads, which included whole families, from grandparents to babies. There were, as Allingham’s biographer, Julia Jones, wrote, “three hundred souls to be accommodated in a village of six hundred and fifty”. Allingham persuaded the villagers to take the families at least for one night. The billeting officer, the local butcher, resigned, and Allingham took over, finding an empty house to turn into a maternity unit. She ordered provisions with a new energy and efficiency, and remarked: “It’s taken me some time to realise it and longer to admit it but so far the war has been my salvation.”

During the first half of 1940, she worked almost furtively on Traitor’s Purse, hiding in the garden, or secreting the manuscript in a biscuit tin during bombings. She wrote: “You’ve no idea how difficult it is to finish a modest thriller when all your neighbours are mucking about in the dawn looking for nuns with sub-machine guns and collapsible bicycles to arrive by parachute.”

Her life was further complicated by a work of non-fiction, The Oaken Heart, which she had undertaken with an American readership in mind, celebrating the threatened English countryside and the English people who were her neighbours.

Allingham had to please agents and publishers on both sides of the Atlantic, as well as magazines such as Collier’s and the Saturday Evening Post, which serialised her work and provided much of the household’s income. Throughout her life, from her early teens, she had sent potboilers and other stories to magazines and papers. She was prolific and earned much of the family’s living by these means. When her recently appointed American agent, Paul Revere Reynolds, saw a synopsis of Traitor’s Purse he was dubious, as he explained, “probably because it was different from most stories and an agent is always scared of what’s different”. But others were more reassuring, and the novel appeared, although in the tense atmosphere of 1941 there seems to have been greater enthusiasm for The Oaken Heart. In fact, no one appears to have thought Traitor’s Purse was unusual, let alone extraordinary.

Yet it is a startlingly good book. It is taut and trim and full of delicious shocks and narrative tension. It is original and moving and amusing. How anyone, working in brief fragments of time, could imagine and hold together the world of this story and tell it infallibly at the right pace is hard to imagine. I do not know if she ever realised what she had done, although she shows intermittent signs of defending her work against critics and editors. In a review in Time & Tide in 1940, she wrote: “the thriller proper is a work of art as delicate and precise as a sonnet”. She knew what she was doing, and what her forms required. But she seems to have had no faith in anyone noticing just how complex and splendid her forms were. When Malcolm Johnson, her American publisher, raised questions about The Fashion in Shrouds (published in 1938), she wrote in a letter: “I now know what I am doing and what I am going to do. I wrote the book intentionally and not by accident and I am going to go on writing similar stories – Malcolm can’t cure me, I’m doing it on purpose.” There are other similar remarks that suggest that she felt her forms were not understood or appreciated.

However, at least one other writer saw how good she was. In 1965, she took part in a “transnational conversation” with John le Carré, whereby she was interviewed in Essex, he was interviewed in Sweden and the copy was cabled to America, for the magazine the Ladies’ Home Journal. Le Carré (real name David Cornwell) sent a telegram to the reporter: ALLINGHAM MARVELLOUS BUT GREATLY REPEAT GREATLY UNDERPLAYS HERSELF. SHE IS A GREAT WRITER WHEN CORNWALL [sic] STILL WASHING ELEPHANTS.

I hope she saw that. She was a great writer.

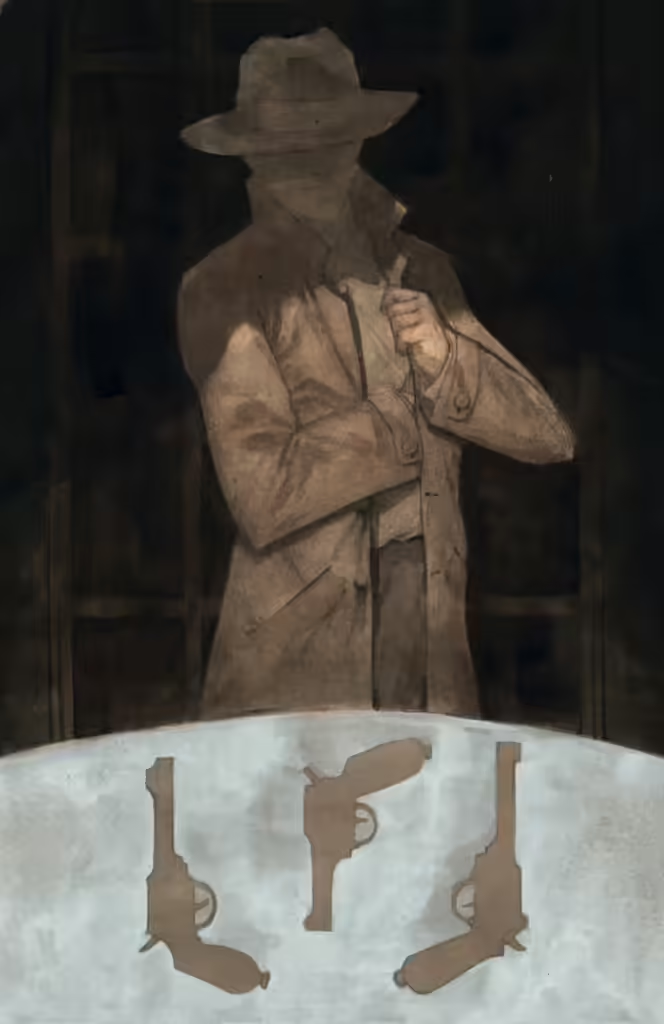

This introduction is from the Folio Society edition of Traitor’s Purse by Margery Allingham, illustrated by James Boswell, published in 2015.

Original article in The Guardian.